The 400 Superamerica delivers speed, beauty and comfort in equal measure.

Story by George Avgerakis, Photos by Dom Miliano

Forza The Magazine About Ferrari December 2005 Number 66

Bella Turismo

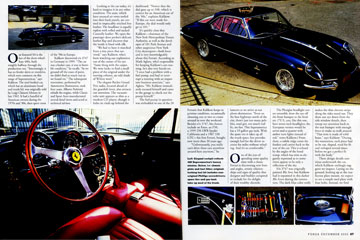

Superamerica – the name says it all. The SAs are big cars with big engines, designed to cover wide-open spaces at triple-digit speeds in comfort. Just the thing for the U.S. market, in honor of which the cars are named. New York City is probably not what Enzo Ferrari had in mind for these machines, but Peter Kalikow and his 1962 400 Superamerica Aerodynamico coupe (s/n 3747SA) live and drive here. We’ve been cruising through Gotham’s canyons for about 20 minutes so far, with Kalikow behind the wheel. The aroma of incompletely combusted hydrocarbons wafts through the elegant cockpit, and we can feel the heat of the Tip 163 4-liter V12 coming through the firewall. “That’s a full-race engine,” Kalikow says, his index finger lifting from the shfit knob to point at our feet. “There’s no exhaust heat shield, so the battery tends to get cooked. We need to replace it frequently.” As he guns the Superamerica into the First Avenue tunnel at around 50 mph, Kalikow suddenly gets a mischievous, slightly guilty grin which belies his 62 years. “In my younger days, when I lived just north of here on First Avenue, I’d come through this tunnel late every night on my way home from work,” he says, the howl of the V12 echoing around us. “I’d often hit a hundred down here before coming out of the tunnel.” The first Superamericas arrived in the mid-1950s, but the name and concept had been introduced by their predecessors, the America series. The first America, the 4.1-liter 340, was a competition car which debuted in 1950. (A 340 Mexico, designed to race in that country’s La Carrera Panamericana, arrived a couple of years later.) A half-dozen 4.1-liter 342 America road cars were built in 1952, followed by a dozen 4.5-liter 375 Americas in 1954. The 5-liber 410 Superamerica debuted at the Brussels Auto Show in February 1956. Over the next three years, three series of 410 SAs were built, in two different wheel-bases and a wide variety of body styles. All told, thirty-five 410s would be produced. At Brussels in 1960, Ferrari introduced a new Superamerica, the 4-liter 400. Production would last for five years, during which time 47 cars in two wheel-bases (2,420 and 2,600mm) and varying bodies were built. The 400 SA received the “small block” Colombo V12—the 410 had utilized the physically larger Lambredi powerplant—fitted with triple sid-plug heads. Ferrari claimed 340 horsepower for the 4-liter engine, the same output as the earlier 5-liter. The 400’s engine and four-speed plus overdrive transmission sat up front in a steel chassis, with the differential and a live axle in back. Front suspension was independent, and telescopic shocks and disc brakes resided at all four corners. The Superamericas were excluxive, evne by Ferrari standards. These cars were built to order for the wealthy and famous, patrons who would help establish Ferrari as the car to own. A quick glance at the list of Superamerica owners reveals names like Agnelli, Volpi, (The Aga) Khan, Riva, Chandon and Bloomingdale. Our featured SA is the last of the short-wheel-base 400s, built roughly halfway through the production run. “Interestingly, it has no fender skirts or overdrive, which were common on this range of Superamericas,” says Kalikow. The steel-bodied car, which has an aluminum hood and trunk lid, was originally sold by Luigi Chinetti Motors in late 1962. It had a handful of American owners during the 1970s and ‘80s, then spent most of the ‘90s in Europe. Kalikow discovered s/n 3747 in Germany in 1999. “The car was a basket case, it was in horrible condition,” he recalls. “As we ground off the coats of paint, we didn’t find so much rust as we found rot.” The subsequent restoration, performed by Automotive Restorations, took four years. Alberto Pedrietti rebuilt the engine, while Classic and Sport “Auto manufactured several detail items and acted as technical advisor. Looking at the car today, it’s hard to imagine it in any other condition. The seats, which have unusual air vents tooled into their back panels, are covered in impeccably stitched fine leather. The headliner is equally replete with rolled and tucked Connolly leather. We open the passenger door, pocket’s delicate leather flap and discover that the inside is lined with silk. “We had to have it matched from a tiny piece that survived,” says Kalikow, who’s been watching our exploration out of the corner of his eye. “Same thing with the carpet. We were lucky to find a small piece of the original under the steering column, an odd shade of Wilton wool.” The elegant Becker Grand Prix radio, located ahead of the gearshift lever, also attracts our attention. The vacuum-tube unit appears as slim as a modern CD player, though it hides its vitals up behind the dashboard. “Notice that the dial goes up to 108, which is correct for an American car of the ‘60s,” explains Kalikow. “If this car were made for Europe, the dial would only go to 101.” It’s quickly clear that Kalikow—chairman of the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority, as well as the developer of 101 Park Avenue and other auspicious New York City skyscrapers—both loves and is very knowledgeable abut this Ferrari. According to Mark Aglora, who’s responsible for keeping Kalikow’s cars running, he’s also very hands-on. “I once had a problem with a fuel pump, and had to interrupt a meeting with an important business associate,” says Aglora. “Mr. Kalikow immediately excused himself and came to the garage to check out the pump himself.” The fuel pump in question was embedded in one of the 28 Ferraris that Kalikow keeps in pristine condition, occasionally choosing one or two to cruise around in over the weekend. Besides s/n 3747, his choices include an Enzo, an F50, a 1959 250 LWB Spyder California and a 1967 330 GTC—his first Ferrari, bought new more than 30 years ago. “Unfortunately, you really can’t drive these cars anywhere around here anymore,” he laments as we arrive at our photo destination. “Even on the best highways north of the city, there’s just too many pebbles, road grit, too much traffic, no fun. This Superamerica has a 33-gallon gas tank. With the spare tire it takes up all the trunk space, but provides enough fuel for the driver to cruise for miles with refueling. And it’s so comfortable.” One of the joys of spending some quality time with a classic Ferrari is discovering new lines and angles, artistic relationships and signs of quality that designer and builder conspired to include for the delight of their wealthy clientele. The Plexiglas headlight covers smoothly draw the eye off the front bumper to the fenders. (“U.S cars, like this one, have seven-inch headlights; the European version would be seven-and-a-quarter with amber turn lights instead of red,” notes Kalikow.) From there, a subtle ridge crests the fenders and carries back to the rear of the car. This is echoed by the angles of the hood scoop, which has trim so elegantly expressed as to sometimes appear to be only a reflection of the sky. S/n 3747 was originally painted Blu Sera, but Kalikow had it repainted in this darker Blu Scuro during the restoration. The dark blue color really makes the thin chrome strips along the sides stand out. The draw our eye down from the side window details, then sweep our attention back to the rear bumper with enough force to make us walk around. “That trim is made of solid brass,” says Kalikow. “During the restoration, each piece had to be cut, shaped, tried for fit and reshaped several times before we got a perfect fit with the body.” These design details continue underneath the car, which Kalikow smilingly suggests we inspect. Laying on the ground, looking up at the rear license plate mount, we expect to see a simple steel plate with four bolts. Instead, we find that Pininfarina fitted a chrome box, its edges extending to mate perfectly with the bumper. “The 400 Superamerica Aerodynamico coupes, to me, represent the high point of Ferrari style in the 1960s,” Kalikow comments as we stand up. “It’s all about the lines. In cars as well as in architecture, if the lines don’t work, it’s worthless.”cv cxds He then gestures off across the East River, apparently towards Italy. “You know, there are some Ferraris, like the 400 SA or the 456, that look best sitting in front of a building designed by the Italian architect Palladio. The lines of the Superamerica and the building just seem to flow back and forth with each other.” We circle the car, with Kalikow answering questions as quickly as we can ask them. When we observe that the tires appear a bit low, he replies, “Full tank of gas.” He then adds, “These are the original Michelin X tires, which are no longer made.” We don’t ask how he got them, because he’s already explained where the Trico Carello windshield wiper arms came from. They were made from scratch, with the companys’ logos engraved according to period photos. Same with the tool kit, which contains both standard and Phillips screwdrivers. We added the “Phillips screwdrivers,” says Kalikow. “In 1962, the Superamerica was a ‘transition’ car. While the factory was still using slot screws, Pininfarina had moved to Phillips screws. You find both on this model.” Likewise, the original operation manual, spec sheets and radio instructions, which are stored in a leather portfolio in the glove box. “I had to replicate a few of these,” Kalikow confesses as he pulls them out. “But I can’t tell which ones.” When we inspect the engine bay, the owner gently spins the radiator fan and points to a small knob with two wires protruding from the water conduit. “There’s a little clutch in the fan’s hub that engages when this temperature sensor hits the right temperature,” he says. “This trick was first used by Peugeot, but Pininfarina also designed for Peugeot, so maybe he went back to Ferrari with the idea. You never know.” We ask Kalikow why he has the large license plate mounted on the front of the car, where it visually interferes with the elegant oval of the egg-crate grille. “This is an American-market Ferrari, restored to its original 1962 condition,” he replies. “It wouldn’t be proper to allow even Pininfarina’s art to supersede authenticity.” He pauses, then adds, “During the years 1952, ’52, ’54, ’55, ’64 and ’65, New York State required only one license plate, in the rear. So if I own a car whose first owner registered the car in New York during those years, I install only the rear plate, and enjoy the front grille as Enzo intended.” The New York State license plate is period-correct orange and black, and reads PSK-1—Kalikow’s initials. (Actually, all of his cars wear a plate with some permutation of those initials.) When we ask if he bought a restoration plate, he replies, “Oh no, most of those plates were on cars our family owned since we were kids. I saved them.” Like many collectors, Kalikow considers himself a custodian of the car, rather than an owner. “I think the purpose of all this restoration is to be able to show, say, a young kid today, just how these cars looked when they were made,” he says. “I remember them as they came out of the factory years ago, looking so great. Maybe they lost the touch a bit in the late ‘70s, but they got it back. Since then, they’ve never lost it.” Actually, s/n 3747 probably looks better than it did when new. Beyond the meticulous restoration, when we notice a tiny bit of thread sticking out from a chrome detail, Kalikow softly asks one of his crew to tweeze it out before the camera lens gets near. Happily, neither that drive for perfection nor New York’s imperfect roads keep Kalikow from enjoying s/n 3747. “It’s comfortable, has a great driving position and a beautifully built body,” he says. “It’s just a fantastic car.”

LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube